Feature image credit to Wikimedia Commons

Now that it’s the summer season, we’re all scrambling to find relief from that intense heat in the water. However, a simple beach day can quickly turn sour. According to a recent CDC study released in May, over 4,500 drowning deaths occurred in the United States each year from 2020 to 2022, leading drowning to be the top cause of accidental deaths worldwide. Unfortunately, these bodies can remain lost for weeks – such was the case for Nicola Bulley in 2014. How then do forensic scientists determine how long a body has been in the water?

On land, estimations of the Post-Mortem Interval (PMI), or the time since a person’s death, are observed through physical changes. Environmental influences are also factored in, which leads to decomposition varying on a case-by-case basis. However, the complications of these calculations compound when a body is found in the water.

The Post-Mortem Submersion Interval (PMSI), or the time since submersion, must factor in the variability of the aquatic ecosystem. Salinity, depth, temperature, water turbulence, and animal activity all play a role in aquatic decomposition. A submerged body could take twice as long to decompose as on land, which could lead to inaccurate PMSI estimates if determined purely by visual observations. Scientists are developing new methods to estimate PMSI to surpass these obstacles and obtain more accurate results.

Researchers from Australia’s Deakin University and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) collaborated on this study to determine how bacterial composition can be used as an indicator of PMSI. They theorized that, depending on the types and abundance of microorganisms inhabiting the necrobiome, crime scene investigation can more accurately determine the stage of decomposition of submerged bodies.

The researchers used three still-born piglets (ethically sourced) per trial to represent the human bodies, and submerged them in tanks of fresh tap water. The salinity, pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), and temperature of the tanks were monitored and recorded during three consecutive one-month trials (T1, T2, T3). Further consideration was given to how clothing would affect the bacterial composition; two piglets wore different shirts made of natural cotton or synthetic nylon, while the last one was unclothed. The researchers collected water samples from each tank and then extracted the bacterial ribosomal RNA (rRNA) to sequence the aquatic necrobiome from the phyla to the genera level (one level above species).

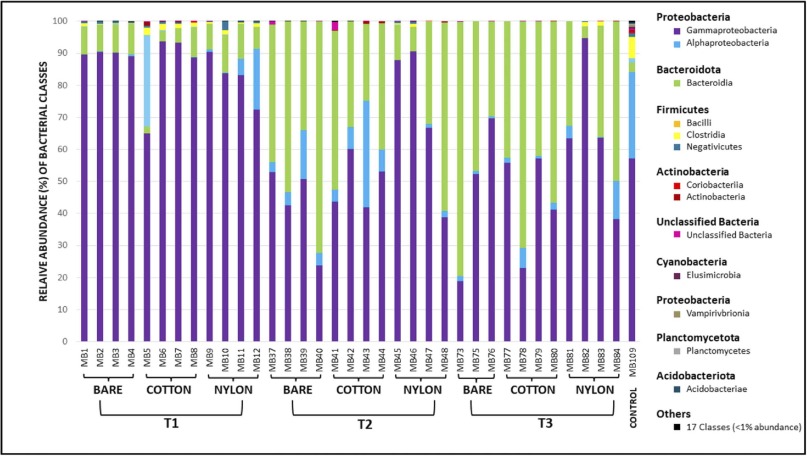

After completing the experiment, the researchers found that the bacterial diversity within the tanks changed over time and temperature. DNA sequencing revealed that the phylum Proteobacteria dominated the water samples of all piglets in the first trial (T1) and showed remarkably little change over time. In contrast, the bacterial population shows a greater presence of Bacteroidota bacteria for the second and third trials, with different patterns; the nylon and cotton clothed bodies showed minimal population shifts during the 4-week sampling period, while the Bacteroidota population of the unclothed body increased over time (Figure 1). The scientists connected these observations to temperature, as the T1 samples were collected during higher average daily temperatures (13.5°C or 56.3°F) than T2 and T3 (~10°C and 12°C respectively). This led the researchers to believe that Proteobacteria prefer warmer environments. Therefore, the type and abundance of bacteria present in the water samples is dependent on the climate conditions.

Bacterial composition not only varied with climate, but also with clothing material. Two bacteria species related to Flavobacterium and Pseudomonas, which characteristically break down dense polymers such as those in nylon, were found in abundance in the nylon samples. Additionally, the cotton samples had lower bacterial growth compared to nylon, attributed to its hydrophilicity and water absorbing properties. As nylon (and human skin) are hydrophobic and water rejecting, there is greater standing water and chance for bacteria growth and biofilm formation. Temperature and clothing clearly influence the bacterial population around the decomposing body, and therefore need to be considered to accurately estimate the PMSI in a wide variety of situations.

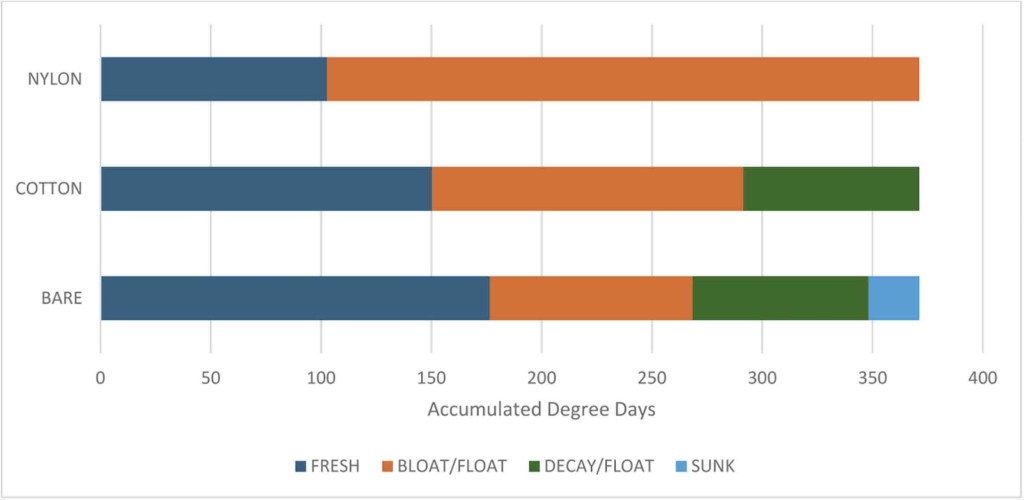

Finally, over the 365 accumulated degree days (ADD), which accounts for the time and water temperature between trials, the scientists observed different effects of body decomposition based upon the clothing type. These included bloating, sinking, and floating. Nylon-clothed piglets bloated faster than the bare and cotton-wearing piglets, but never fully entered the decay stage. The researchers theorized that the nylon material created a preservation layer between the body and the water due to its hydrophobic properties, like wrapping something in plastic film. They also explained the faster bloating as a result of the nylon concentrating the heat inside the body due to limited breathability of the fabric, though this result could change with different weaves of the material. The bare piglets, on the other hand, exhibited the shorter bloating/floating phase and reached the decay stage the fastest, eventually sinking. Similar to the bare piglets, the cotton-wearing piglets also reached the decay stage, but like the nylon-wearing piglets, never sank.

Despite being conducted over a single season, this study by Bone et al. demonstrates how temperature differences alone are enough to impact microbial populations. However, the study also showed how not only the environment, but also the clothes someone is wearing, can influence decomposition and microorganism abundance. Further research should be done to investigate how scavenger activity and insects play a role in aquatic decomposition. Though piglets do not accurately represent human decomposition, the work provides a good foundation to expand to human trials, such as at a body farm, and helps to define the current limitations of PMSI calculations.

| Title | Aquatic conditions & bacterial communities as drivers of the decomposition of submerged remains |

| Authors | Madison S. Bone, Thibault P.R.A. Legrand, Michelle L. Harvey, Melissa L. Wos-Oxley, Andrew P.A. Oxley |

| Year | 2024 |

| Journal | Forensic Science International |

| URL | https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0379073824001531 |