Source for header: “Sand Australia Gold Coast” by PeterKopias is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Glass particles are notoriously difficult to study since they are small and nearly invisible. A Dutch research group is using glow-in-the-dark sand to study glass particle transfer.

Many invisible interactions happen at a crime scene. The perpetrator deposits fingerprints; fibers from a rug cling to the victim’s clothing; soil from the offender’s shoes is left behind. Another less common, but equally important, trace transfer is that of glass. When glass shatters, hundreds of tiny, nearly invisible particles transfer onto nearby surfaces. Forensic analysts can use these glass particles to place individuals at crime scenes, but information beyond that is minimal. This is because tiny glass particles are just that: tiny glass particles. However, the Jap van der Weerd group at the Netherlands Forensic Institute believe that glass particles can shed more information on an individual’s movements at a crime scene if analyzed in a new way.

Currently, if glass particles are found on a piece of clothing, an analyst must remove the glass to manually count it. This is time-consuming and only gives information about the number of particles, which may hint when and to what extent a contact occurred. The van der Weerd group believes that the patterning of the glass particles on clothing can provide information about the type of contact the perpetrator may have had with the crime scene. For example, glass particles may transfer from a perpetrator’s jacket onto nearby jackets if hung on a shared coat rack. Information about this type of transfer can be useful in quickly tracking down a suspect or collecting other clues about a crime.

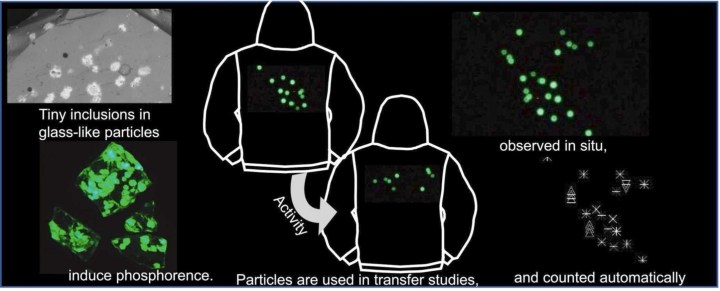

Limited information on glass transfer exists because of how difficult glass particles are to see. The van der Weerd group developed a system to study glass particle transfer using glow-in-the-dark sand as a model for glass particles. The sand, normally sold as a toy, has the same chemical composition as soda-lime glass, the most common type of glass produced. The sand has small pockets of strontium complexes, a metallic compound that is phosphorescent (Figure 1). When UV light shines on it, the strontium stores energy and releases it over a long period of time as blue-green light. This helps researchers quickly identify the glass on clothing without removing it first.

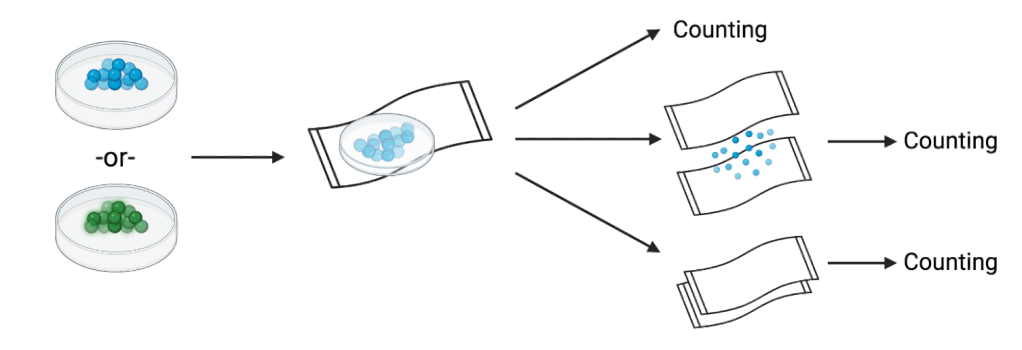

First, the group needed to ensure that their glow-in-the-dark sand particles would act the same as regular glass particles. To do this, they tested how the particles transferred between different surfaces (Figure 2). The first experiment examined how well each type of particle transferred from a small dish onto a piece of cloth. Researchers rubbed the dish onto the cloth and counted the number of glass particles using an automated counting system, which was just as accurate as manual counting but much faster. Their results showed that the sand transferred the same as the glass, and allowed the group to use the sand as a “proxy” material. Without this step, researchers would not be able to make comparative claims about the glass particles when using their sand substitute. More detailed experiments further tested whether the sand could substitute the glass by testing secondary transfer, finding minimal difference in terms of how the glass and the glow-in-the-dark sand behaved. This meant that the glow-in-the-dark sand acts as a good model for glass transfer.

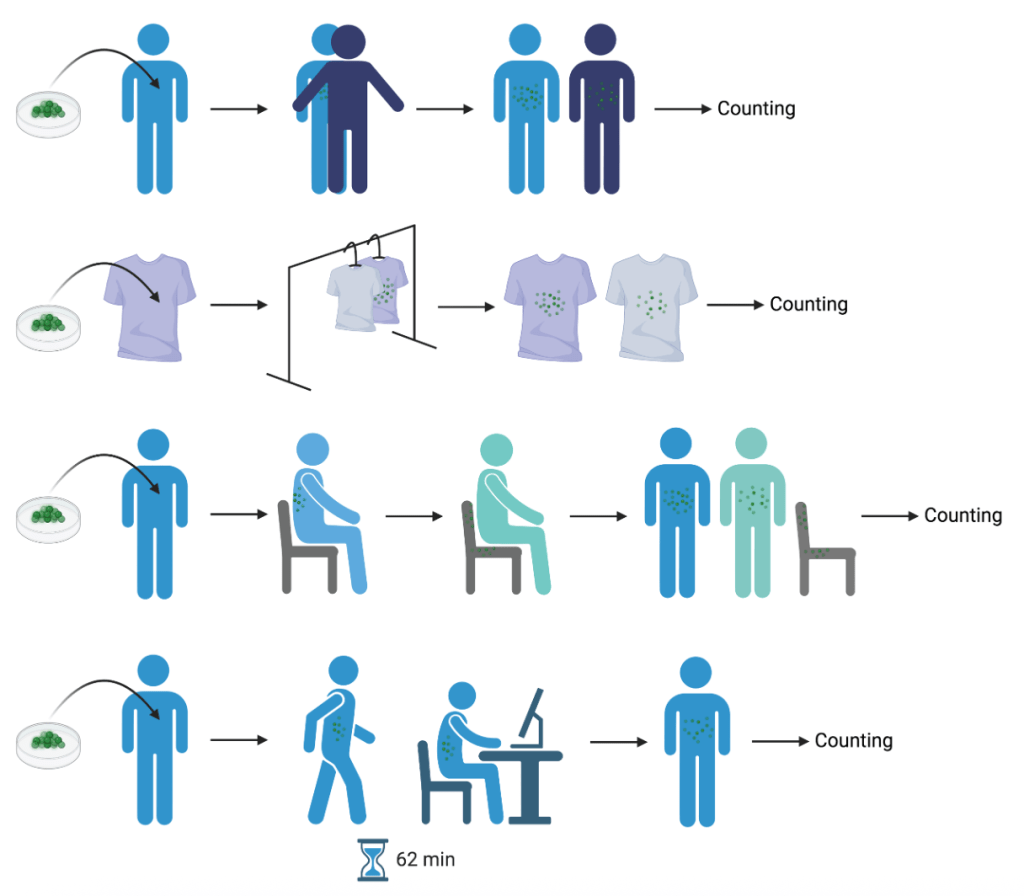

Further experiments enacted different transfer scenarios using the glow-in-the-dark sand model to test how secondary transfer could occur. These scenarios included “hugging”, “coats hung next to each other on a coat rack”, “chair transfer” (where someone sat in a glass-contaminated chair after the first person left), and “continued use” (where someone with glass on their clothing performed regular work activities) (Figure 3). The glow-in-the-dark sand allowed researchers to quickly examine how many particles transferred from the donor, the person considered to be at the crime scene, to the recipient, someone unrelated to the crime, in each of these scenarios. The researchers found that in most of the activities, very low numbers of glass particles transferred between the donor and recipient. Most importantly, however, they determined that their glow-in-the-dark sand methodology, coupled with their quick phosphorescent imaging technique, allowed the researchers to test multiple different scenarios very quickly compared to traditional techniques of glass transfer testing.

The glow-in-the-dark sand system acts as an easy way to test a variety of scenarios in record time. Instead of having to remove each individual piece of glass from an article of clothing, the forensic analyst can quickly recreate any scenario in the lab and test how glass particles behave specifically. This will allow for faster turnover of evidence and the expansion of current knowledge on how glass particles transfer between surfaces.

| Title | A pilot study into the use of phosphorescent sand in glass transfer studies |

| Authors | Rik Aulbers, David Redder, Carlijn M. van den Pol, Peter D. Zoon, Jaap van der Weerd |

| Journal | Forensic Science International |

| Year | 2024 |

| URL | https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0379073823003109 |