Source for feature photo: Edward Jenner hosted by Pexels.

Imagine you’re a new forensic biochemist who just completed their on-site job training (after a four-year STEM degree and hands-on internships, of course) and are ready to aid your county’s investigations with your technical prowess. On your first day, you receive evidence from the field: a biological sample on a cotton swab. No problem, you know what to do – extract the DNA, quantify the amount present, amplify the 20 gene markers that make up the CODIS DNA profile, and then obtain said profile from capillary electrophoresis (CE) sequencing (our ForensicBites overview of the DNA profiling process is here!).

But then you hit a snag; only 8 of the 20 genetic markers show up, and with low signal intensity. That’s unexpected, so you consult with your technical supervisor, who recommends that you run your reference standards to ensure the method and instrument functioned as intended. The standards come back with their high-quality results, leaving you mainly with data interpretation issues, now that you’ve eliminated certain sources of technical error. It’s likely that the sample you analyzed was from a degraded source, based on the number of markers missing from your profile. And unfortunately, a partial profile like this could prove useless to exclude suspects from (or strongly link them to) the crime scene.

Laboratory techs do not encounter this problem on the regular – but when they do, the consequences can greatly hinder criminal investigations. The forensic community therefore works together to handle these problems by sharing information on best methods and practices.

This includes various government agencies, such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and their forensic subdivision OSAC (Office of Scientific Area Committees for Forensic Science). At its core, NIST ensures standardization – providing assessments, training workshops, and materials to guarantee high-quality results produced by federal agencies. Their mandate covers areas from artificial intelligence and biomedicine, to electronics, manufacturing, and physics. The staff in forensics, including powerhouses John Butler and Sandra Koch, also perform various fundamental studies and coordinate nationwide initiatives for integration of science-backed forensics analysis and transparent communication in courtrooms.

Recently, NIST created a new category of reference standards, called Research Grade Test Materials or RGTMs, to expand the catalog of materials that scientists can use to avoid inconclusive data interpretation. Normally, references standards ensure technical function of the method or instrument and reproducible and accurate data interpretation. However, these RGTMs function a bit differently; you can imagine that if you created a degraded DNA sample, the sample may just continue to degrade and become unreliable. Therefore, although the 8-sample RGTM 10235 set was validated and released to the forensics community in 2023, NIST just published the results of their study in 2024 – ensuring that their reference standards were stable and reliable over the period of a year.

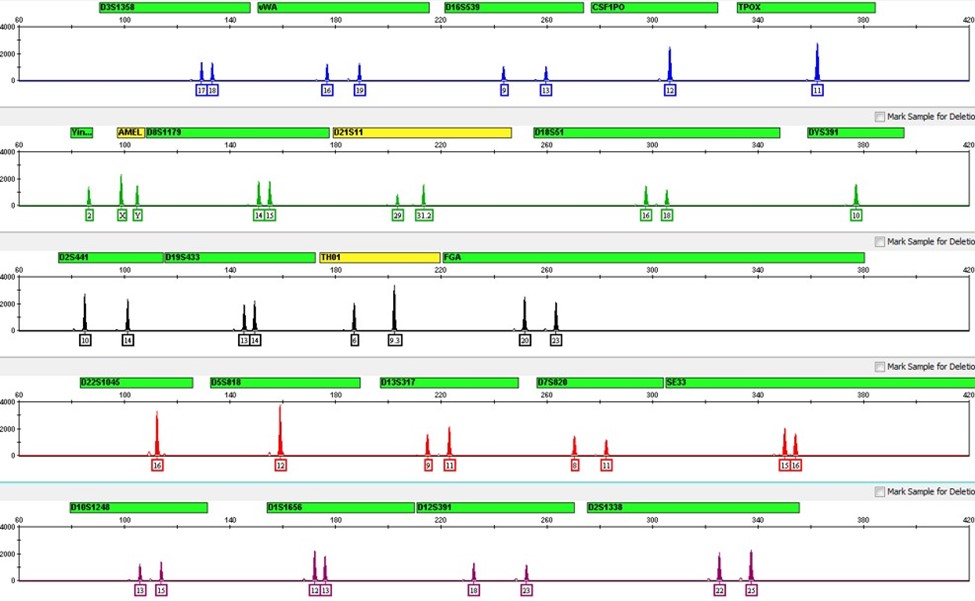

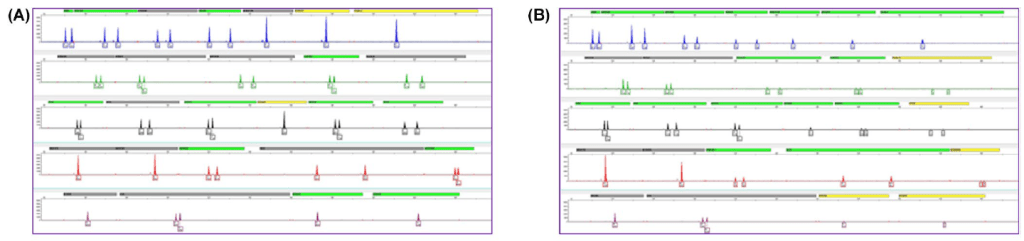

The scientists in the Applied Genetics Group at NIST, who completed the study, produced degraded female and male DNA extracted from blood using UV light, which disrupts and mutates the bonding between our DNA strands. The non-degraded sample produced sharp, high intensity peaks for all 20 gene markers analyzed (Fig. 2A); in comparison, the degraded sample had less intense peaks for the longer genetic markers, with some disappearing entirely (mainly the last three genetic markers in black; Fig. 2B). However, both samples produced consistent profiles with consistent DNA quantity over the period of a year, demonstrating their long-term stability when properly stored in a fridge.

Interestingly enough, for both nondegraded and degraded male DNA samples, the NIST scientists included yeast tRNA. When DNA is extracted, the non-nucleic acid material is kept in solution while the nucleic acid is precipitated out using organic solvents. Yeast tRNA can improve the overall recovery of DNA, as it will also crash out with the human DNA and make the precipitant visually bigger. That way technicians are more likely to recover as much DNA as possible, and the tRNA is not amplified with the DNA primers nor recognized during DNA sequencing, making it an effective but inert additive.

Another important aspect of reference standards is consistent results between labs. That’s why the NIST division collaborated with the Bode Technology Group, a forensic-based company, to ensure the reproducibility of their findings. Fortunately, the company found that DNA profiles and quantification of the RGTM set matched closely with what the NIST scientists published, which indicates that the validated RGTM could replace the internally-collected standards that local labs use. Internally collected standards are good for quickly performing local tests, but inhibit method standardization across large regions and hinder open sharing practices, typically due to lower quality of record keeping. Transparently sourced and accessible reference standards can aid standardization and open sharing practices while also improving courtroom scientific testimony. If everyone uses the same definition obtained from the same material, then variable interpretation between practitioners decreases, providing a fairer environment in the courtroom for evidentiary presentation.

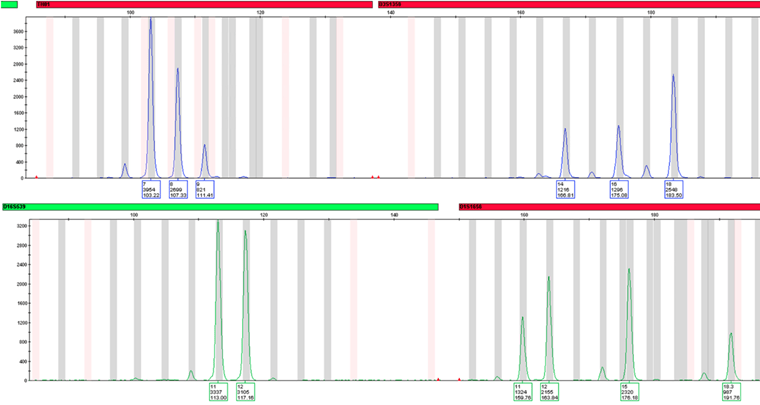

In addition to degraded DNA, RGTM 10235 also includes three complex mixtures samples – one of male and female DNA in equal parts, and two samples of two male and one female DNA at different ratios. Interpretation of DNA mixtures relies on the proper amplification of each contributor or donor, and the ratio between the peaks to denote the donor as major or minor. Since each donor can only contribute at most two peaks per genetic marker, the presence of more than two peaks strongly indicates multiple donors (Fig 3). If two donors have completely different peaks per genetic marker, it is entirely possible to identify both profiles at all DNA markers – and some genetic markers have upwards of twenty different peak possibilities! Identifying all profiles in a mixture can be especially important for crimes involving multiple perpetrators, such as in the cases of sexual assault or murder.

The success of RGTM 10235 can provide a basis for the further production of complex standards and encourages communication between the forensic case examiners in the field and the method developers at NIST. Most importantly though, it can provide high-quality training for current practitioners to improve their data interpretation skills of complex DNA mixtures and degraded samples.

| Study title: | Development of a forensic DNA research grade test material |

| Study authors: | Erica L. Romsos, Lisa A. Borsuk, Carolyn R. Steffen, Sarah Riman, Kevin M. Kiesler, Peter M. Vallone |

| Journal published: | Journal of Forensic Sciences (published by Wiley) |

| Year published: | 2024 |

| URL | https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1556-4029.15639 |

| Open access? | Yes! No paywall |